9.5 Mass Defect and Energy

Consider the masses of subatomic particles:

- proton = 1.00727 amu

- neutron = 1.00866 amu

- electron = 0.00055

If we wanted to calculate the mass of a helium-4 atom (2 protons, 2 neutrons, and 2 electrons), one might perform the following calculation:

\[m_{\mathrm{He~atom}} = (2 \times 1.00727~\mathrm{amu}) + \left ( 2\times 1.00866~\mathrm{amu} \right ) + \left ( 2 \times 0.00055~\mathrm{amu} \right ) = 4.03296~\mathrm{amu}\]

However, careful mass spectrometry measurements indicate that the mass of a helium-4 atom is 4.002602 amu (see NIST), one of the most precisely known masses (see Table 3 in 2003 IUPAC, Pure and Applied Chemistry 75, 683–800). We quickly conclude that the measured mass of a helium-4 atom is lighter than the sum of its parts! This difference between these two masses is called the mass defect (Δm). If we think about this in terms of a typical reaction, we have

\[ 2~^1_1\mathrm{p} + 2~^1_0\mathrm{n} + 2~^{\phantom{-}0}_{-1}e ~\longrightarrow ~^{4}_{2}\mathrm{He}\]

to give the following mass defect

\[\begin{align*} \Delta m &= \mathrm{mass~of~products} - \mathrm{mass~of~reactants}\\ &= 4.002602~\mathrm{amu} - 4.03296~\mathrm{amu}\\ &= -0.030358~\mathrm{amu} \end{align*}\]

There is nothing incorrect with the measured values of the subatomic particles or the mass of the atom. So what is going on? Albert Einstein demonstrated that the mass of an object is directly proportional to its energy and is described using the mass-energy equivalence equation.

\[E = mc^2 \quad or \quad \Delta E=\Delta mc^2\] where

- m is the mass defect

- c is the (two-way) speed of light in a vacuum (approximately 3.00×108 m s–1)

- E is the energy equivalent to the mass defect

In short, any energy change is accompanied by a change in mass and vice-versa. This applies to everything from nuclear reactions to celestial bodies. Mass that is lost is converted to energy and energy that is lost is converted to mass.

9.5.1 Mass defect in nuclear reactions

Let’s look at our He-4 forming nuclear reaction again. Fusing the subatomic particles together causes a loss in mass. This mass is converted into energy.

\[2~^1_1\mathrm{p} + 2~^1_0\mathrm{n} + 2~^{\phantom{-}0}_{-1}e ~\longrightarrow ~^{4}_{2}\mathrm{He} \qquad \Delta E < 0 \propto \Delta m < 0\]

We can determine the energy of this nuclear reaction per mole of He created using the known mass defect.

First, convert the mass defect of one helium-4 nucleus into the mass defect of one mol of helium-4 nuclei.

\[\left( \dfrac{-0.030358~\mathrm{amu}}{\mathrm{atom}} \right ) \left ( \dfrac{1.66\times 10^{-27}~\mathrm{kg}}{\mathrm{amu}} \right) \left ( \dfrac{6.022\times 10^{23}~\mathrm{atom}}{\mathrm{mol}} \right ) = -3.035\times 10^{-5}~\mathrm{kg~\mathrm{mol^{-1}}}\]

\[\begin{align*} \Delta E &= \Delta mc^2 \\[1.25ex] &= (-3.035\times 10^{-5}~\mathrm{kg~mol^{-1}})( 3.00\times 10^{8}~\mathrm{m~s^{-1}} )^2\\ &= -2.73\times 10^{12}~\mathrm{kg~m^2~s^{-2}~mol^{-1}}\\ &= -2.73\times 10^{12}~\mathrm{J~mol^{-1}}\\ &= -2.73\times 10^{9}~\mathrm{kJ~mol^{-1}} \end{align*}\]

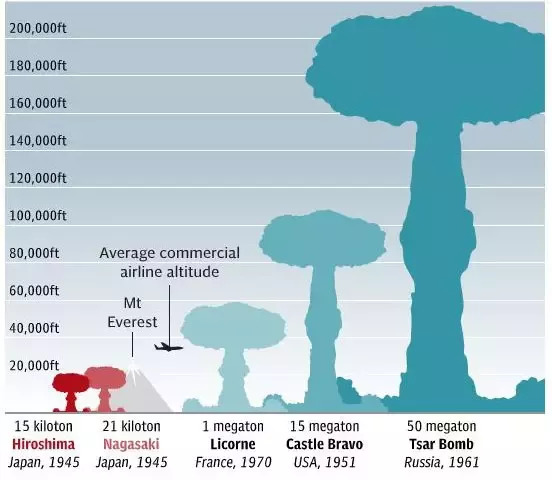

When one mole (or approximately 4 grams) of helium-4 is created from its constituent subatomic particles, a staggering 2.73×109 kJ of energy is released. Compare this to Castle Bravo, the largest thermonuclear weapon ever detonated by the US, which had an energy yield of about 15 Megatons of TNT (or about 6×1013 kJ or 63 PJ).

)](files/ch21/Castle_Bravo_Blast.jpg)

Figure 9.6: Castle Bravo Test (from Wikipedia)

Figure 9.7: Comparison of some nuclear bomb yields

Due to the very small energies associated with nuclear reactions on a per atom basis, energy is usually expressed in units of megaelectronvolts (MeV).

For our He-4 nucleus formation reaction above, the mass defect for one helium-4 nucleus is equivalent to 4.535×10–15 kJ released shown here.

\[\dfrac{2.73\times 10^{9}~\mathrm{kJ}}{\mathrm{mol~He}} \left ( \dfrac{1~\mathrm{mol~He}}{6.022\times 10^{23}~\mathrm{He~atoms}}\right ) = 4.53\times 10^{-15}~\mathrm{kJ~/~He~atom}\]

Convert this energy from kJ to MeV.

\[4.535\times 10^{-15}~\mathrm{kJ} \left ( \dfrac{1~\mathrm{eV}}{1.602\times 10^{-22}~\mathrm{kJ}} \right ) \left ( \dfrac{1~\mathrm{MeV}}{10^6~\mathrm{eV}} \right ) = 28.3~\mathrm{MeV}\]

This is equivalent to the nuclear binding energy of the nucleus of a helium-4 atom (i.e. the energy required to split a single He-4 nucleus into its constituent subatomic particles is 28.3 MeV).

We can break this down even more into MeV per nucleon to get the average amount of nuclear binding energy holding a pair of nucleons together in an atomic nucleus. The helium-4 atom has 4 nucleons (2 protons + 2 neutrons).

\[28.3~\mathrm{MeV}/\mathrm{4~nucleons} = 7.1~\mathrm{MeV~nucleon}\]

This MeV/nucleon notation is a measure of the stability of an atomic nucleus. The higher the binding energy (per nucleon), the more stable the nucleus.

9.5.2 Mass defect in chemical reactions

Mass changes can be applied to chemical reactions, though the lost mass is too small to have any non-trivial effect on the properties of the reaction. Consider a chemical reaction such as the combustion of graphite to produce carbon dioxide (Exercise adopted from LibreTexts).

\[\mathrm{C(graphite, s)} + \frac{1}{2}\mathrm{O_2}(g) \longrightarrow \mathrm{CO_2}(g) \qquad \Delta H^{\circ} = -393.5~\mathrm{kJ~mol^{-1}}\] We can determine the mass change in this reaction by employing our mass-energy equivalence equation.

\[\begin{align*} \Delta E &= \Delta mc^2 \\[1.25ex] \Delta m &= \dfrac{\Delta E}{c^2} \\[1.25ex] &= \dfrac{-393.5~\mathrm{kJ~mol^{-1}}}{\left ( 3.00\times 10^{8}~\mathrm{m~s^{-1}} \right ) ^2}\\[2ex] &= \dfrac{-3.935\times 10^5~\mathrm{J~mol^{-1}}}{\left ( 3.00\times 10^{8}~\mathrm{m~s^{-1}} \right ) ^2}\\[2ex] &= \dfrac{-3.935\times 10^5~\mathrm{kg~m^2~s^{-2}~mol^{-1}}}{\left ( 3.00\times 10^{8}~\mathrm{m~s^{-1}} \right ) ^2}\\[2ex] &= -4.37\times 10^{-12}~\mathrm{kg~mol^{-1}}\\ &= -4.37\times 10^{-9}~\mathrm{g~mol^{-1}} \end{align*}\]

We see that for every mole (12.011 g) of graphite consumed, about a billionth of a gram of mass is lost. This loss of mass for chemical reactions is too small to measure.

9.5.3 Fusion

We have seen with our helium-4 example that combining subatomic particles to create an atomic nucleus creates (releases) energy due to a loss of mass. Fusion is the process by which nuclei of atoms are fused together to create a heavier nucleus. This can occur when two very fast moving nuclei slam into each other with sufficient energy. These nuclear processes generate a tremendous amount of energy on the macroscale (see Hydrogen Bomb). Light atoms tend to undergo fusion to increase the stability of its nucleus (and release energy in the process).

)](files/ch21/Deuterium-tritium_fusion.png)

Figure 9.8: The fusion of deuterium and tritium to form helium-4 (Image from Wikipedia)

9.5.4 Fission

Fission is the opposite of fusion. It is the nuclear process by which an atomic nucleus is split into smaller, lighter nuclei. Heavy atoms readily undergo fission as their nuclei are rather unstable (higher in energy than they want to be). Energy is released when this process occurs (see Atomic Bomb)

)](files/ch21/fission.jpg)

Figure 9.9: The fission of uranium-235. (Image from OpenStax)

9.5.4.1 Example: Fission

Uranium-238 is unstable and radioactive but with a long half-life. It undergoes α decay.

\[^{238}_{\phantom{0}92}\mathrm{U} ~\longrightarrow ~^{234}_{\phantom{0}92}\mathrm{Th} +^{4}_{2}\mathrm{He}\]

The mass defect (Δm) is –0.004584 amu which means that mass is lost and converted to energy. Determine the energy (in kJ and eV) per atom and the energy (in kJ) per mole of uranium-238 decay.

Energy released per uranium-238 atom

Convert the mass defect from amu to kg.

\[-0.004584~\mathrm{amu} \left ( \dfrac{1.66\times 10^{-27}~\mathrm{kg}}{\mathrm{amu}} \right ) = -7.6094\times 10^{-30}~\mathrm{kg}\]

Convert the mass (in kg) into kJ and MeV.

\[\begin{align*} \Delta E &= \Delta m c^2\\ \Delta E &= (-7.6094\times 10^{-30}~\mathrm{kg})(3.00\times 10^{8}~\mathrm{m~s^{-1}})^2\\ &= -6.850\times 10^{-13}~\mathrm{kg~m^2~s^{-2}} \\ &= -6.850\times 10^{-13}~\mathrm{J}\\ &= \color{red}{-6.850\times 10^{-16}~\mathrm{kJ}} \left ( \dfrac{\mathrm{eV}}{1.602\times 10^{-22}~\mathrm{kJ}} \right ) \left ( \dfrac{\mathrm{MeV}}{10^6~\mathrm{eV}} \right ) \\ &= \color{red}{-4.276~\mathrm{MeV}} \end{align*}\]

The nucleus (i.e. system) lost 4.276 MeV of energy (hence the negative symbol) and the surroundings gained a +4.276 MeV of energy.

Energy released per mole of uranium-238

Now we know how much energy is released per atom. Use Avogadro’s number to determine the energy released (in kJ) per mole of uranium-238.

\[\dfrac{6.850\times 10^{-16}~\mathrm{kJ}}{\mathrm{atom}} \left ( \dfrac{6.022\times 10^{23}~\mathrm{atoms}}{\mathrm{mol}} \right ) = 4.125\times 10^{8}~\mathrm{kJ~mol^{-1}}\]

We see that when one U-238 atom undergoes an alpha decay, a very small amount of energy (6.850×10–13 kJ) is released. When one mole of U-238 atoms undergoes an alpha decay (approximately 238 g), a staggering amount of energy (4.125×108 kJ) is released.